Spoilers ahead for the series premiere of Westworld, so if you aren’t caught up with “The Original,” feel free to take care of that now. I’m fine waiting – I can use the time to wrangle all these devils back into hell.

A few years ago, when I first heard that Michael Crichton’s 1973 film Westworld was being adapted into an HBO series, I was pretty excited. Westworld was one of those childhood touchstone movies for me, because it had everything a young boy could want: sci-fi action and adventure, all in an Old West setting (as a child, I never understood why someone would want to go to Roman World or Medieval World when they could go to Westworld instead). Yul Brynner was terrifying as the AWOL AI “Gunslinger,” who spent most of the movie hunting down the film’s protagonists before being killed (after several failed attempts) by the mustachioed good guy.

As I got older, I would return to the film every now and then, but with each subsequent viewing, I began to notice more and more things about it that bothered me. I’ll never say Westworld is a bad film – I still love it for all the same reasons I loved it as a kid – but from my adult perspective, I began to see the film’s missed opportunities. The most troublesome of these missed opportunities was that we were never told why Yul Brynner’s AI went off-script and began gunning down the guests. He was a one-note villain who never spoke a word, which was enough to make the film fun, but not interesting. I’m not trying to bag on Critchton’s script here – as with all his other works, this one featured groundbreaking ideas that were ahead of their time – I’m just saying there was plenty of good storytelling that didn’t get a chance to be told.

But now, thanks to HBO and showrunners/husband and wife team Jonathan Nolan (The Dark Night, Person of Interest) and Lisa Joy (Burn Notice), Westworld is getting the treatment this fanboy always hoped it would: the AI of the futuristic theme park are finally getting a voice.

In “The Original,” it becomes quickly apparent that the show will feature storylines that are unfolded through the AI’s perspective (in the Westworld universe, AIs are called “hosts,” while their human customer counterparts are called “newcomers”). We learn in the premiere that host Dolores Abernathy – played with a ferocious grace by Evan Rachel Wood, who will undoubtedly get an Emmy nod next Fall – is the oldest host in all of Westworld: the original. For most of the premiere, we the viewers are sutured to her point of view, and we learn that she, like all other hosts in Westworld, exist in a sort of Groundhog Day loop in which they relive the same day over and over again, though each day has slight variances based on the whims of the newcomers.

As Dolores moves through her day, we watch as she interacts with her world in and around the western town of Sweetwater. Wood shines throughout all of it; there’s no doubt that she’s connected with Dolores’s character. Though she’s an android, it’s impossible not to connect with the humanity that’s buried within her lines of code. Her reaction shots, like when seeing Teddy Flood (James Marsden) for the first time (again) every day, or when she hears a gunshot coming from her father’s (Louis Herthum) homestead, aren’t just on-point – they’re god damned immersive. Wood can draw you in without uttering a single word, imbuing her with a humanity that surpasses many of the actual human guests bustling around her.

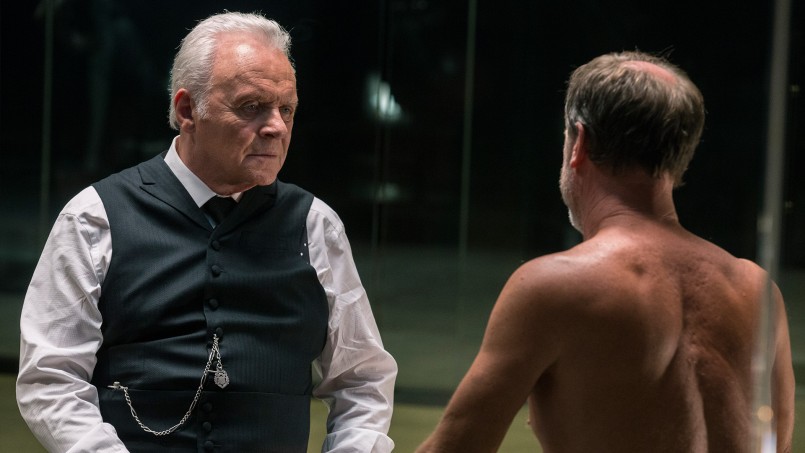

If Dolores and Teddy are our first connections to the hosts of Westworld, then our first connection to their human overlords are lead programmer Bernard Lowe (Jeffrey Wright) and Westworld creator and mastermind Dr. Robert Ford (Anthony Hopkins). We learn that Ford has recently added code sequences to the hosts that imbue them with hyper-real mannerisms and tics, which takes the AIs to a bold new level of human verisimilitude. But when some of the hosts begin to go extremely off-script, it becomes clear that there may have been something in the code that makes the hosts a little too human.

Lowe, along with facilities director Theresa Cullen (Sidse Babett Knudsen) and lead scriptwriter Lee Sizemore (Simon Quarterman), begin to realize that Ford may be losing touch with reality, and begin to anticipate the day that Ford steps down, or, more likely, is deposed from his position. Everyone seems to have their own plans for the future of Westworld, but now that the hosts are poised on the cusp of fully-realized self-awareness thanks to Ford’s code, it’s anyone’s guess as to how things will shake out in the futuristic resort.

The final prominent role in the premiere belongs to the mesmerizing Ed Harris, who plays the cold-as-ice Man in Black. Though the costuming is directly based on Yul Brynner’s outfit from the original film, that’s where the similarities stop (aside from each character’s penchant for drawing blood, of course). The Man in Black is a human – a newcomer – though the handle hardly applies here, since the Man in Black has been coming to Westworld for thirty years. Though he clearly gets off on the violence he doles out in Westworld, it seems that the Man in Black is in search of a deeper mystery hiding somewhere in the brick-red hills surrounding the town of Sweetwater.

To talk about the Man in Black, we have to talk about the rape narrative built into the premiere. Early in the episode, the Man in Black kills Teddy (for the umpteenth time) before dragging Dolores into the barn to rape her (again, for the umpteenth time). Featuring rape – or the threat of rape – in TV and movies is always a slippery slope. Often times it’s blatantly mishandled as something to simply add shock value, but in the case of Westworld, I think the showrunners are doing their best to give an honest portrayal of how humans would behave if they were given carte blanche to behave however they want (“People don’t come here to see who they are,” says Dr. Ford. “They come here to see who they want to be”). Showrunner Lisa Joy sheds some light on how they approached sexual violence when writing Westworld:

When we were tackling a project about a park with a premise where you can come there and do whatever desire you want with impunity and without consequence, it seemed like an issue we had to address […] Sexual violence is an issue we take seriously; it’s extraordinarily disturbing and horrifying. And in its portrayal, we endeavored for it to not be about the fetishization of those acts. It’s about exploring the crime, establishing the crime and the torment of the characters within this story and exploring their stories hopefully with dignity and depth and that’s what what we endeavored to do.

I really like the approach that Joy is talking about here, and I think that having a female co-showrunner like the talented Joy making these sorts of narrative decisions is the right way to go.

I can’t begin to explain how excited I am for this show. I love the philosophical questions the show has already started to bring up, particularly those surrounding the question of what makes us fundamentally human, and what happens when those fundamentals begin to break down. Westworld is a place where humans can go to shed our humanity – our ethics, our morals, our ingrained understanding of the the difference between Right and Wrong, Good and Evil. But as the biologically human guests become less human, it seems that the AI hosts are moving closer to the great renaissance when they become fully self-aware, and when that happens, holy shit will things get real.

5/5 stars: Between an all-star cast, excellent writing, and a jaw-dropping production value, I have no doubt that Westworld will emerge as one of the greatest shows on television.