Another week has gone by, and there have been another string of terror attacks in the Middle East. In Turkey, we saw armed men detonate a series of suicide bombs in the terminal of Istanbul’s Ataturk airport before turning automatic rifles on the crowd inside.

On Sunday, the deadliest suicide car bombing in history rocked Baghdad’s Karada district, killing 250 people.

Both events were granted relatively little attention in western media. It’s become a familiar refrain to hear in the wake of terror attacks in the Muslim world: “Why does no one seem to care when Muslims are the victims of terror attacks?”

It’s a fair question, and one without an easy answer. Compared to the sort of outpouring of support shown throughout the world in the aftermath of the Paris attacks, few tears have been shed publically for the dead of Iraq. After Paris, buildings

After Paris, buildings from Shanghai to Brazil, including the White House, lit up with the shades of the Tricouleur to show solidarity with the French people.

After the bombings this weekend, the White House remained a uniform white.

So does the western world seem to care more about attacks against other westerners, as critics allege? Any unbiased observer would have a hard time arguing that this is not the case.

So with the basic premise behind it established as true, let’s get back to the question itself and ask why it is that attacks in Istanbul don’t result in Facebook profile filters and attacks in Brussels do.

It’s not an easy question to answer, and perhaps an impossible one to answer definitively, but I think we can make a few general observations.

First, humans are strange when it comes to empathizing with others. We can feel enormous grief for the suffering of others, even those we have never met. Yet it seems that we only possess this capacity to empathize with others when we can find some way to relate to them. We can emphasize with friends, with family, with people in Paris, yet only when we feel connected to them. Without getting too analytical, we seem to divide the world into “Us” and “Them”. We can sympathize with “Us”, the people in Western societies. We can sympathize with people who remind us of ourselves. But, we don’t seem as capable of sympathizing with the other. With people who, subconsciously, we associate with terrorists themselves.

And that is the crux of the matter. Even the most enlightened intellect has a hard time overcoming this basic impulse to tribalism. Most of us know that the overwhelming majority of Muslims around the world do not support terrorism. Yet we see that one link, religion, the thing we most associate with the terrorists who attack us, and lump everyone who shares that religion into the same tribe. And since 9/11, we have decided that this tribe is our enemy.

In the darkest, most primal part of our beings, we think that these people are not us, and thus they are not people.

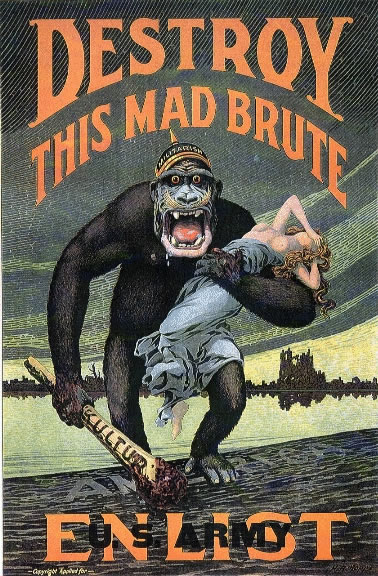

We dehumanize people we consider to be enemies. It’s what we have always done. It’s why propaganda posters of WWI depict Germans as beasts.

It’s why American Marines in the Pacific collected skulls from dead Japanese soldiers to send home to their sweethearts.

It’s always been like this. How do you convince your soldiers to kill an enemy if they think of them as just some poor scared kid like they are?

Furthermore, the frequency of these events tends to stifle what little bit of sympathy we manage to defy our lizard brains to muster. “There are terrorist attacks in the Middle East,” we think. “That’s just what happens. It’s been that way as far back as we can remember. How can you get upset about something that is basically supposed to happen.”

And in a sense that’s true. Iraq sees far more terrorist attacks and sectarian killings in a year than America has in several lifetimes.

Last year over 17,ooo people died in sectarian violence in Iraq. That’s almost 6 times as many people died on 9/11. And it happens every year. Since the invasion of Iraq as many as 200,000 Iraqis may have died.

If anything the frequency of this violence should make us more sympathetic. Instead, it makes us less so.

And when apportioning television coverage, you spend the most time on subjects your viewers want to see. When people don’t care about a subject, you move on, because you depend on viewers to make money, and news has always been first and foremost a business.

Do Muslims deserve to be attacked? Are they reaping the consequences of their support for jihadist terror?

Of course not. The vast majority of Muslims don’t support terrorism.

So is Islam itself the cause of terrorism? Hardly. There is a complex series of political and ideological factors that leads someone to commit a terrorist attack. Right now the most visible terrorists are the ones motivated by their interpretation of Islam, but terrorist attacks have been committed in the name of everything from protecting unborn fetuses to a united Ireland.

Right now Muslims are bleeding for the rise of jihadist terrorism as much as, if not more than, everyone else. And yet they endure suspicion as well as violence for the implicit association we make between them and the people blowing them up.

And our refusal to show grief when Muslims die is not only a moral issue, but a practical one. The singular message of IS and other terrorist groups to Muslims is, everyone in the world is against you, and we are the only ones fighting back. When our subconscious reaction to these tragedies seems to confirm this message, we give it undeserved legitimacy.

Muslims are not our enemy, often they are fellow victims. They are people, just like everyone else, trying to go about their lives. They want to go to work; they want raise their children to have things a bit better than they did; they want to go on vacations; they want to be safe, just like we do.

When those men strode through the airport in Istanbul, casually gunning down women and children, Muslim victims hid in terror and prayed to be spared along with victims of every religion. When those bombs exploded in Iraq, Muslim mothers pulled aside rubble to search for the broken bodies of their children the way any mother would.

Let’s try to sympathise with them. It’s the least we can do. Let’s not make grief, or our refusal of it, a weapon.